Undulating moorlands, punctuated by trickling streams and dense forests of holm oak and silver birch; great, otherworldly bottle ovens, still just about churning out pottery in the face of imported ceramic from abroad; Alton Towers, Drayton Manor, the Trentham Monkey Forest; terrier dogs, dogged football; Robbie Williams. The county of Staffordshire has a number of storied claims to fame, yet a former wrestler’s fifty-room country estate-cum-Buddhist retreat might just be the weirdest. But that was why I found myself in an imported Japanese people carrier, hurtling down the winding country lanes that cut through the Hawksmoor woods just outside of Stoke-on-Trent, on a dark and drizzly Tuesday morning in March. I was on my way to meet Kendo Nagasaki at his Moor Court Hall home in Oakamoor.

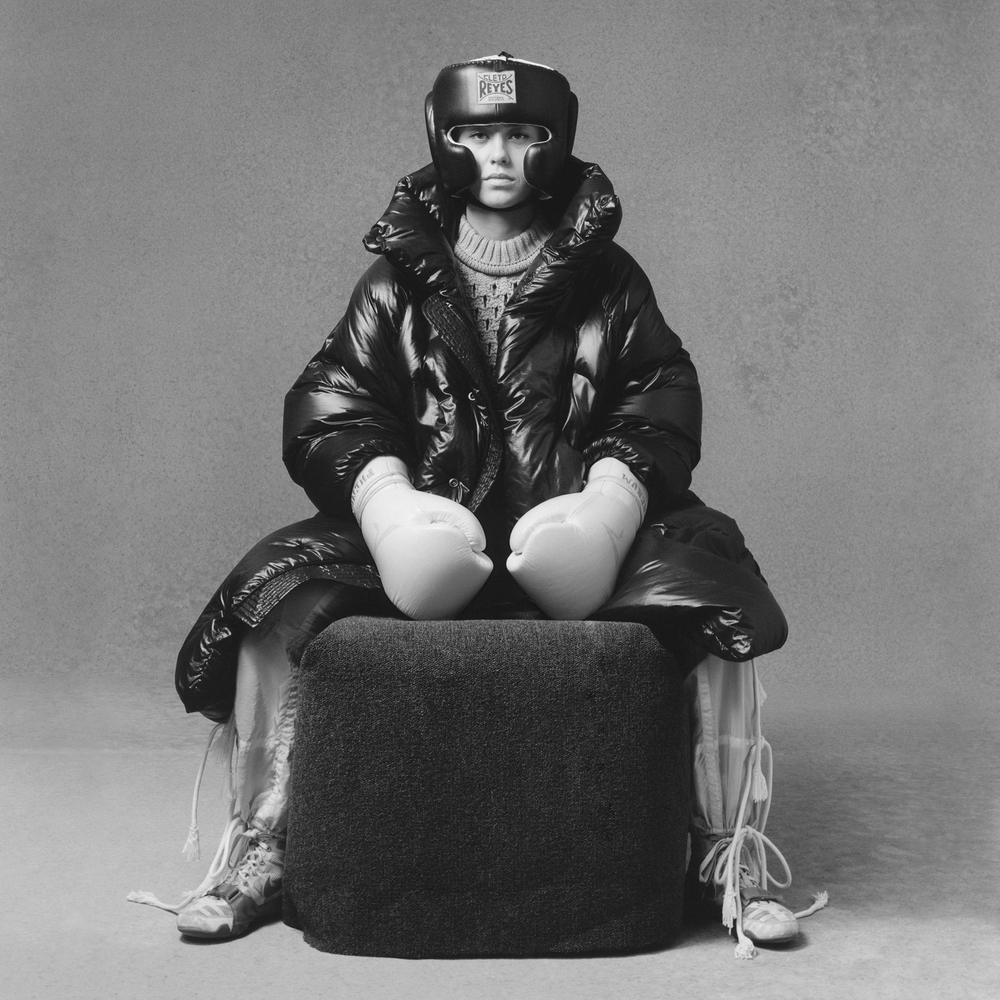

There was once a time when Kendo Nagasaki was a British household name; as synonymous with wrestling then as The Rock or Stone Cold Steve Austin were around the turn of the millennium. Every Saturday afternoon during the sepia-tinted seventies, millions of people would tune in to ITV’s World of Sport to watch the mute, masked Nagasaki wrestle alongside Big Daddy, Wayne Bridges, and Giant Haystacks. British wrestling had really taken off ten years previously with the introduction of televised matches, but it was the heel Nagasaki who made it fun – up until his ITV debut in 1971, wrestlers had largely been big, burly, boring blokes in lycra. Kendo Nagasaki was an enigma; a villain; a character: a silent samurai in an unnerving striped mask with half an index finger, who was as vicious in the ring as he was mysterious out of it. Who was he? Rumours abounded in playgrounds and pub lounges across the country. That he was deformed following a fire and hid his scars with the mask. Or that he was a mystic healer from the Far East. Or he was Prince Phillip. The truth was somehow even more peculiar than any fiction. At his hotly-anticipated ceremonial unmasking in 1977, it was discovered that the man underneath the mask was just as uncanny as the kendo-inspired cloth itself. When his then-manager, ‘Gorgeous’ George Gillette, removed the black and white vizard after a bizarre ritualistic ceremony, he revealed a strange, red-eyed westerner with an occult star tattoo on the top of his shaved head, and a jet-black ponytail protruding from the back.

By the early 2000s, owing to a well-publicised land dispute with a neighbour of Moor Court Hall, it was fairly common knowledge that Kendo Nagasaki was actually a man named Peter Thornley, although it wasn’t until 2018 and the publication of his autobiography, Kendo Nagasaki and the Man Behind the Mask, that Thornley began to speak publicly. Now eighty-one years old, I wanted to find out more about Thornley the man – his history as Nagasaki is well documented, but what about life away from the ring? What moves and motivates Peter Thornley? What does he get up to now he’s retired? So, one weekday morning I took the train from Euston up to Stoke and, after being picked up and driven east for forty-five minutes, found myself sitting outside his imposing grey-bricked home in the middle of England.

Moor Court Hall is massive. Work began on the estate in 1860 at the behest of Alfred Bolton, a senior partner in Thomas Bolton & Sons copperworks which employed much of the nearby village of Oakamoor. The company supplied the copper that, two years earlier, had been laid under the Atlantic as part of the first transatlantic telegraph cable, and erection of the grand, Jacobean revival mansion was an equally expensive operation. Comprising fifty rooms and a number of annexes and separate lodges, the property is set amongst large, well-maintained grounds, where alpacas and horses idly graze. In 1957 it was sold to the Home Office, and became a Women’s Correctional Centre and open prison. Peter Thornley purchased the property in 1989, and it was he who greeted me as the rain began to lash down and I stepped out of the people carrier.

Thornley cuts an imposing figure even in his eighties. At six foot two, and with big, broad shoulders and a full head of hair, he’s almost as fit now as he was back in his wrestling heyday. Dressed in a fine two-piece tracksuit, there was a touch of the agèd athleisure cool of The Sopranos’ Paulie Gualtieri to him – if Paulie had a strong, gruff Stokey-Crewe accent, rather than a New Jersey drawl: “come in and have a seat – would you like a cup of tea?” he asked, with a wry kindness completely at odds with the videos I’d seen of him in action. I was quickly ushered into his office, in what used to be the library of Moor Court Hall. In the corner of the room, facing outwards, is his desk – a great, Resolute-style executive with a vintage Kendo Nagasaki poster positioned under the glass top. Almost every inch of the room is covered in wrestling paraphernalia: old masks, signed photographs, awards, merchandise, statues, bric-à-brac. Peter Thornley sat behind his desk, observing me observing the room.

“How do you want to do this then?” he asked me. And with that, he was off. On the drive over to the house, my chauffeur for the day and one-time mouthpiece of Kendo Nagasaki, Roz Macdonald, had told me that once Peter got started talking, he was quite hard to stop; fond of going off on broadly-connected tangents, leaving you with no chance of steering the conversation back on topic. This, frankly, is an interviewer’s dream, and sure enough, after my first question we spent a good forty-five minutes discussing his early wrestling career, without me ever having to ask any follow ups. The topline was thus: Peter Thornley was born Brian Stevens in 1941, given up by his birth family, and adopted by the Thornleys. Childhood was made harder by both the death of his adopted mother when he was aged seven, and his profound dyslexia, an affliction that caused him much shame and frustration throughout his life. As a teenager, he was a boxing champion who also took up judo, studying under sensei Kenshiro Abbe. Like virtually every physical activity that Thornley threw himself at as a youngster, he excelled, but it was under Abbe where his interest in philosophy, meditation, and eastern teachings was piqued. He still meditates to this day, “twice a day… when [he] wants to”. The Kendo Nagasaki character was created, and the story goes that in a state of deep meditation Thornley contacted the spirit of a 300-year old samurai warrior, who he channelled in the ring. In 1964 he had his first professional wrestling match as Kendo Nagasaki, and so started a career that saw him fight, on-and-off, with unmaskings, remaskings, and at least two lengthy retirements, until 2008.

But what about away from the ring? Just like the rumours of who Kendo really was under the mask, I’d heard a variety of stories about Thornley’s life outside of wrestling. In his autobiography – the proceeds of which, fascinatingly, went to the Lee Rigby Foundation, a charity set up in the wake of Rigby’s 2013 murder to help bereaved military families – he revealed that he was bisexual. “I used to go out to dances with my friends, and I’d find that rather than looking at the girl I’m with I’m looking at my mate”, he told me. “I thought that everybody was like that, because we never got taught anything about homosexuality. Nowadays it’s everywhere – I’ve got a gay hotel and bar in Blackpool”. He’s referring to the Trades Hotel, a male members-only hotel that provides a retreat for gay men to socialise and make new acquaintances. It’s not the only business venture Thornley’s had over the years. In the 1980s he managed Laura Pallas, a Hi-NRG singer who toured with Divine. He’s always had car dealerships, including one on Stockwell Road in London, where he hung out with the Richardson gang: “They liked me because I was Kendo. I wasn’t a gangster, but I was a tough guy, and they gravitated towards tough people”.

It’s a personal history that sounds too farfetched to be true – the bisexual wrestler who hung out with gangsters and managed drag-adjacent disco acts, who then aligned himself with the family of the most famous victim of terrorism in England – but he assures me it all happened. After almost an hour of talking, I felt like Thornley had warmed to me. He was by now speaking at length about his charity work, which he’s particularly proud of: “I’ve got the Kendo Nagasaki Foundation, which teaches the principles of kyu shin do – Kenshiro Abbe’s methods to achieving zen – to guests who stay with us here at the house”, he said. Whilst these retreats have been curtailed by the pandemic, Thornley’s other charitable endeavour has been thriving. “Now I’m involved with the learning disabilities side of things, Kendo’s Day Care”, which is a day support facility for adults in the Staffordshire area with learning disabilities and autism. “I understand what it’s like to really want to do something, but not being able to – having struggled myself with my dyslexia. It’s a bastard. Because you can’t get around it. I have empathy for them”, he told me. It’s clear this is a subject he feels passionately about, and his voice wavers as he discusses it. “I know that it’s difficult for these people who I’m trying to help. We should do the best we can for them. I owe it to myself. I owe it to them, really”.

The daycare sees groups come to Moor Court Hall in the mornings and afternoons, four days a week, to take part in a number of activities aimed at enriching and empowering their lives. The daycare was in session today, and he wanted me to see how it all worked. Thornley called his long-time assistant and partner, Lawrence Stevens, into the office. He was keen for me to meet Jacques, a young participant in Kendo’s Day Care, and sent Lawrence off into another wing of the house where the programme was happening. The week previously, CircleZeroEight’s photography team had been up for an overnight stay, and Jacques had shown a keen interest in the clothes featured in these photos. Jacques was a chatty lad of twenty-eight, a passionate Stoke City fan, very bright and engaging, and a favourite of Thornley’s. When he spoke to Jacques, there was a calm, pedagogic gentleness in his voice. I thought back to the unmasked Kendo of 1977, and wondered if back then that red-eyed hitman could have ever imagined helping people full-time in his eighties. “I understand it. I want to make their dreams come true”, he told me of the daycare. “I’ve come a long way from where I was. People think I’ve done very well for myself, and perhaps I have. But it was a difficult journey, and I know that these people that I try to help and encourage have difficult journeys of their own”.

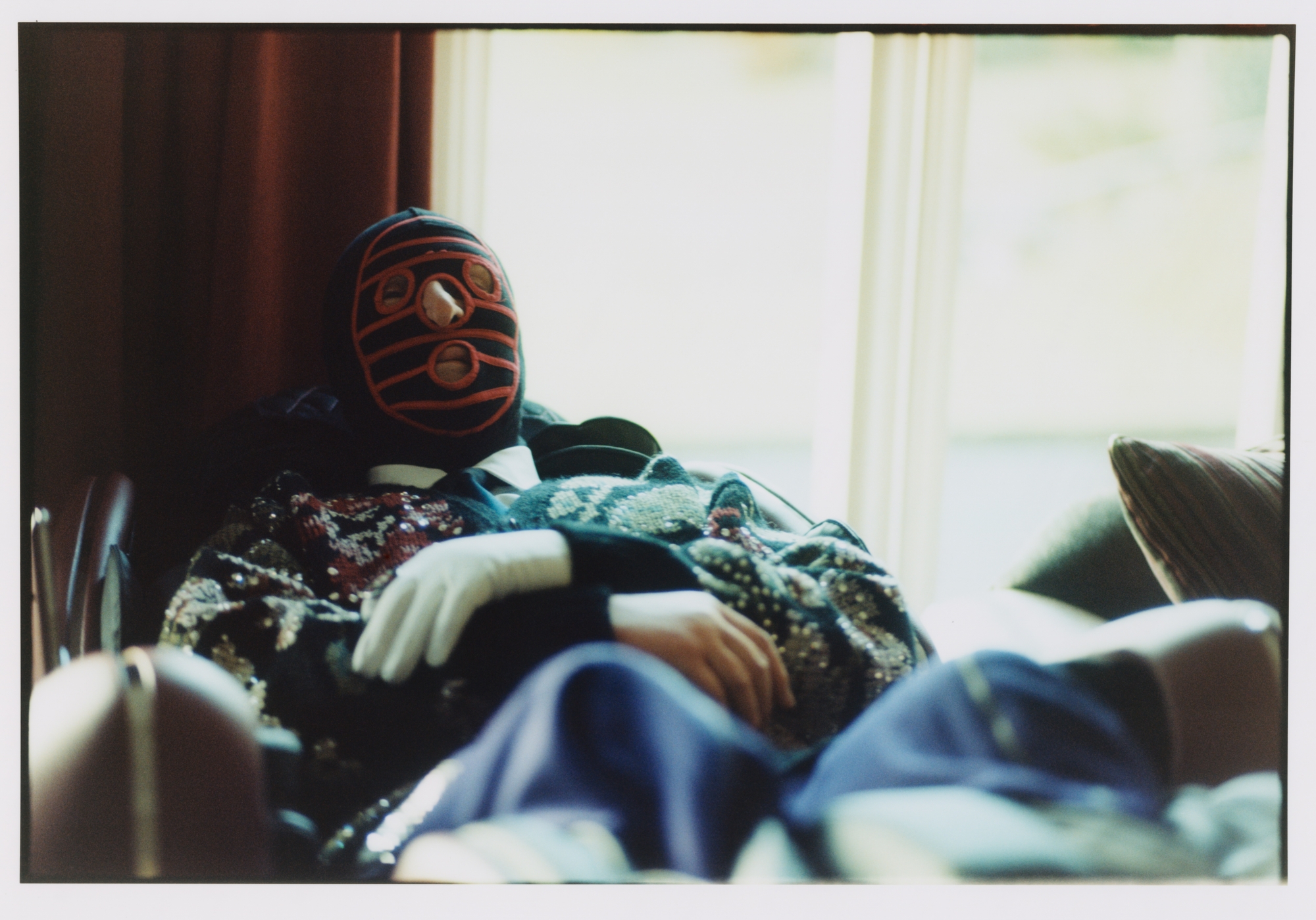

Interview over, we retired to another room to have fish and chips from nearby Cheadle. We ate with the rest of the daycare gang, and lunch was a cacophony of jokes, laughter, and playful arguing. At the head of the table, away from it all, quieter now as others shouted, was Peter Thornley. Or perhaps it was Kendo Nagasaki, silent, deep in meditation. In the corridor outside the dining room, in a perspex case, are all the Kendo Nagasaki costumes. Walking past the display after lunch, I realised it was hard to divorce a character as powerful as Kendo completely from your life; Kendo was in many ways Peter.

It was time to go. I left Peter in his office, and made my way back to the people carrier for the return leg to Stoke station. It had started to rain again, and I was conscious that we were cutting it fine to make my train. As Roz and I pulled out down the drive, we could see the daycare crew were also now getting ready to leave. It’s a strange world at Moor Court Hall, but it’s a world of fun, education, and genuine affection and care. A fitting coda to the life and career of a truly fascinating man.