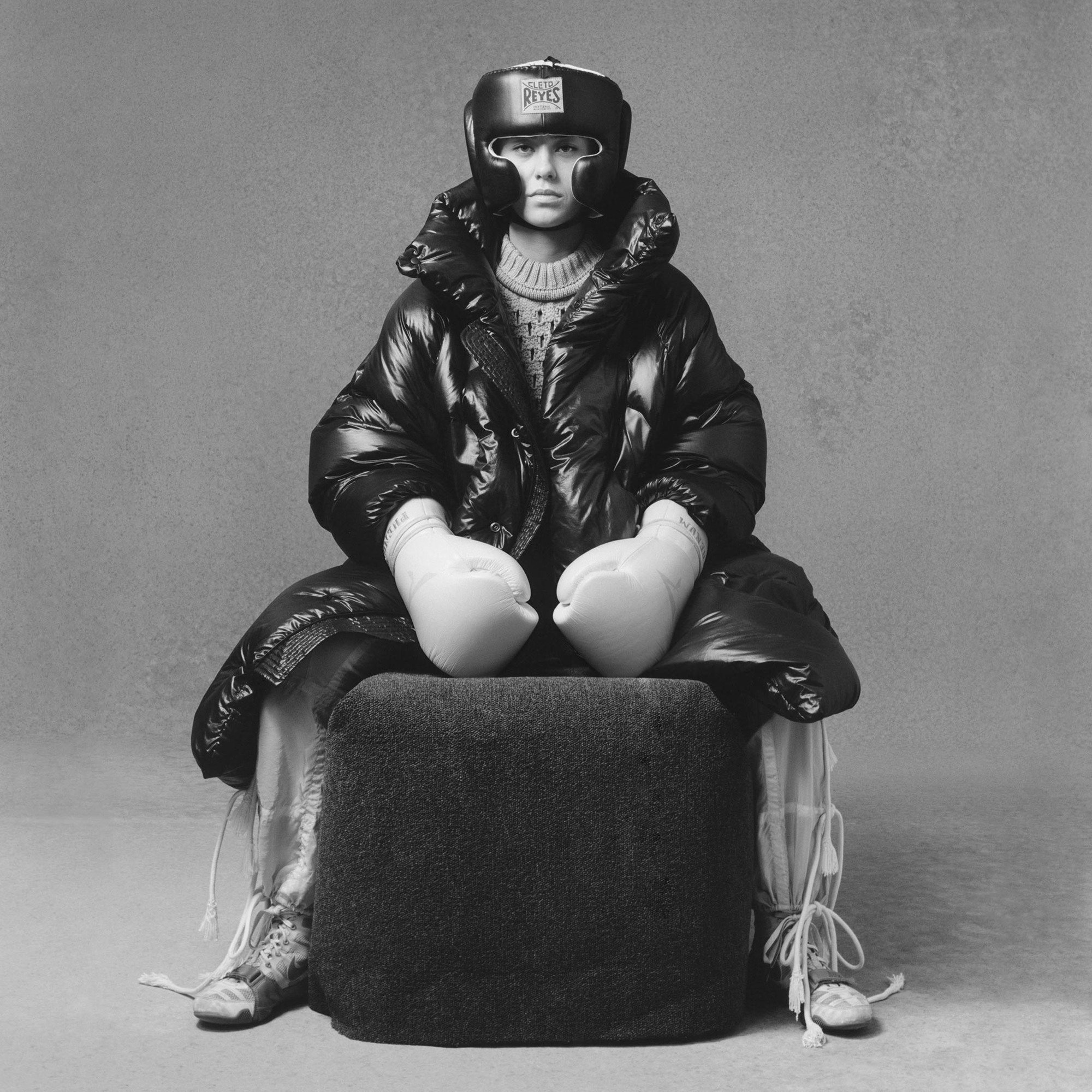

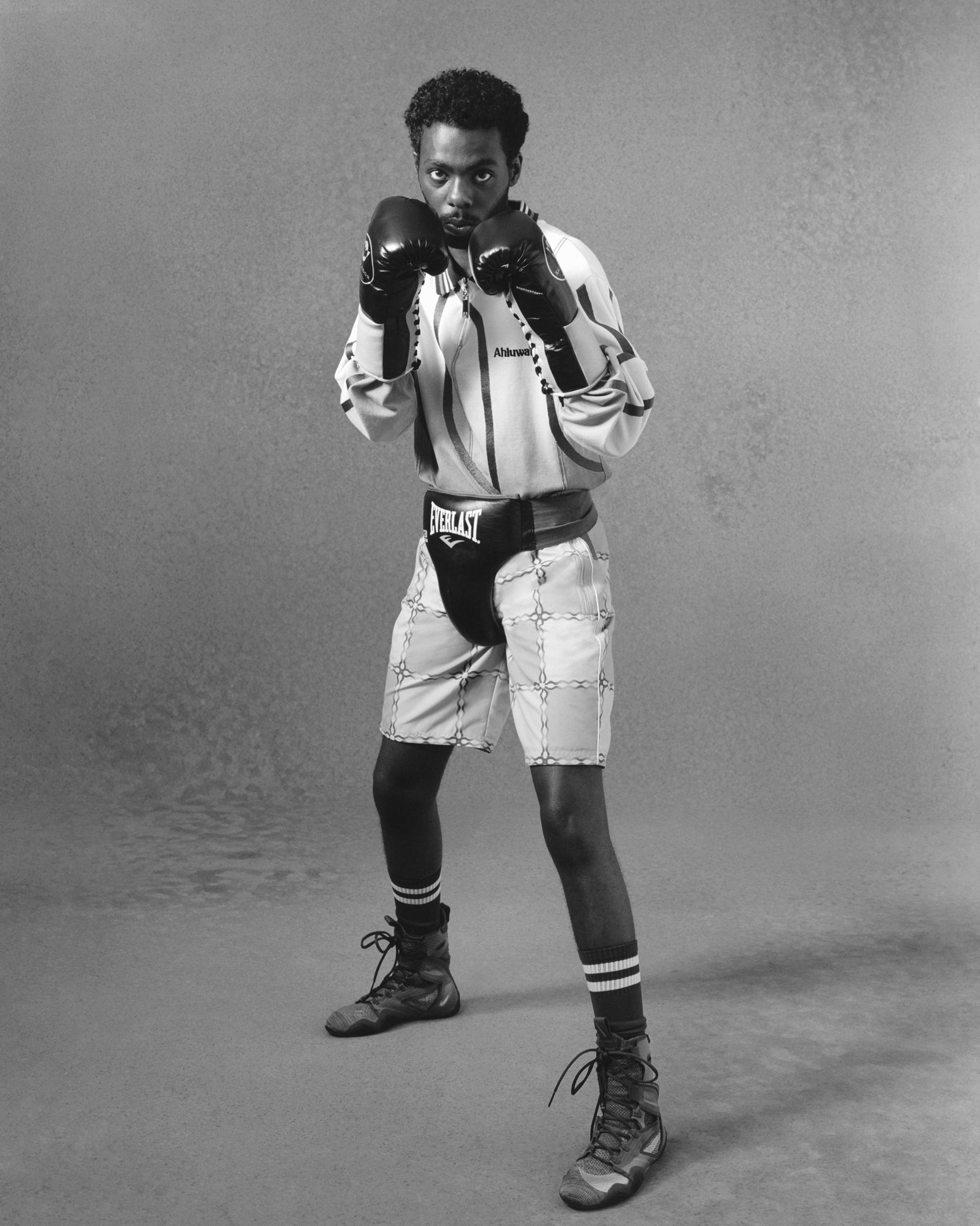

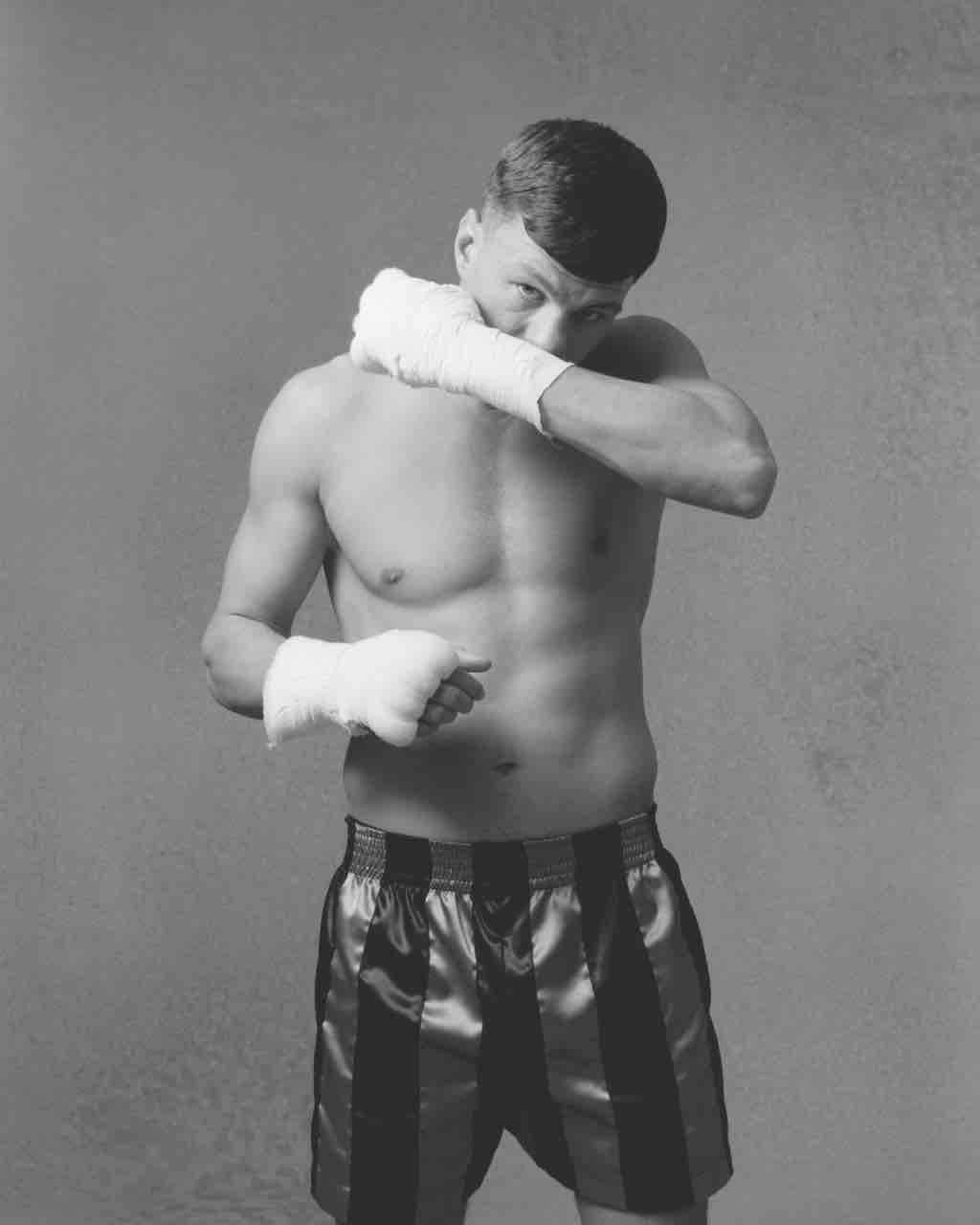

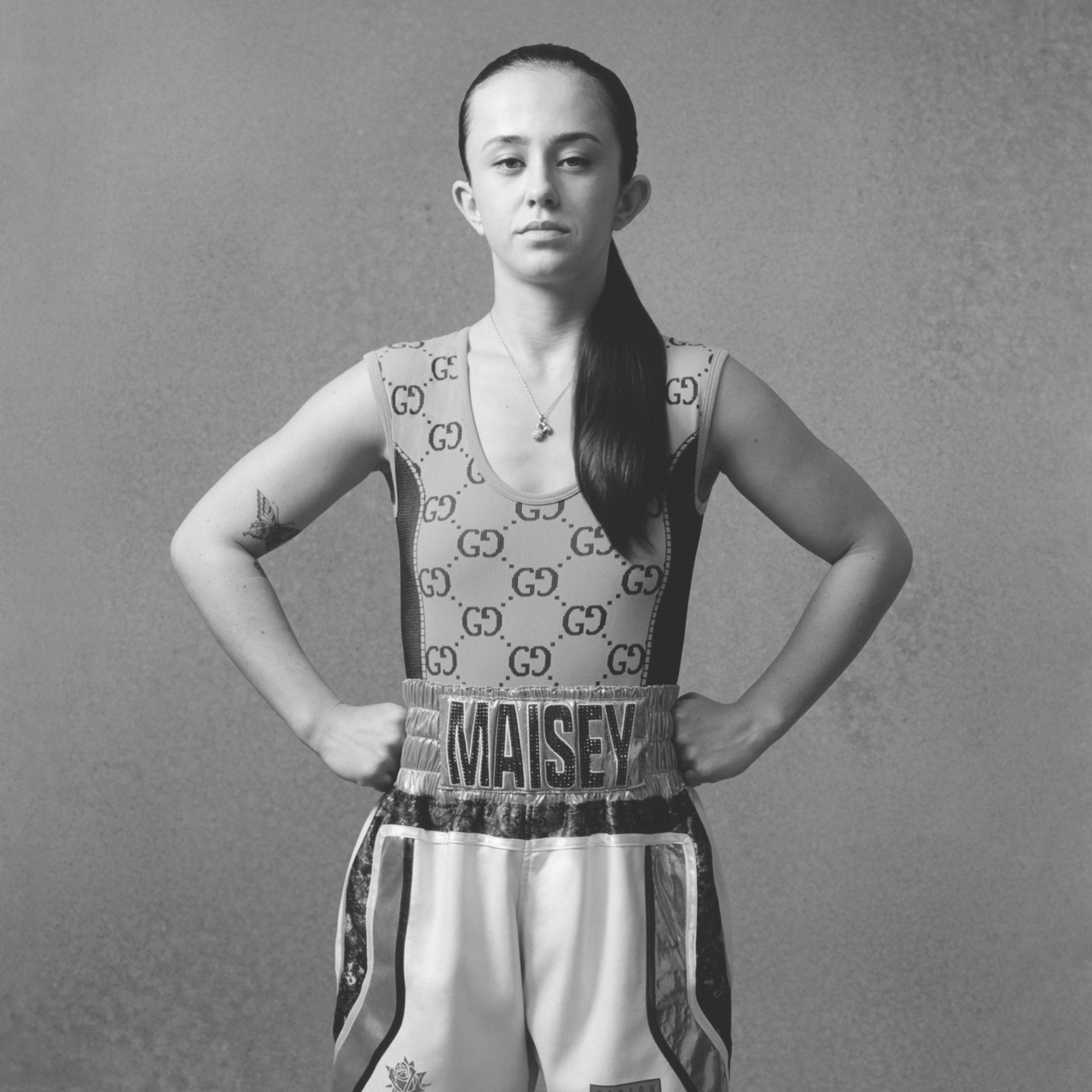

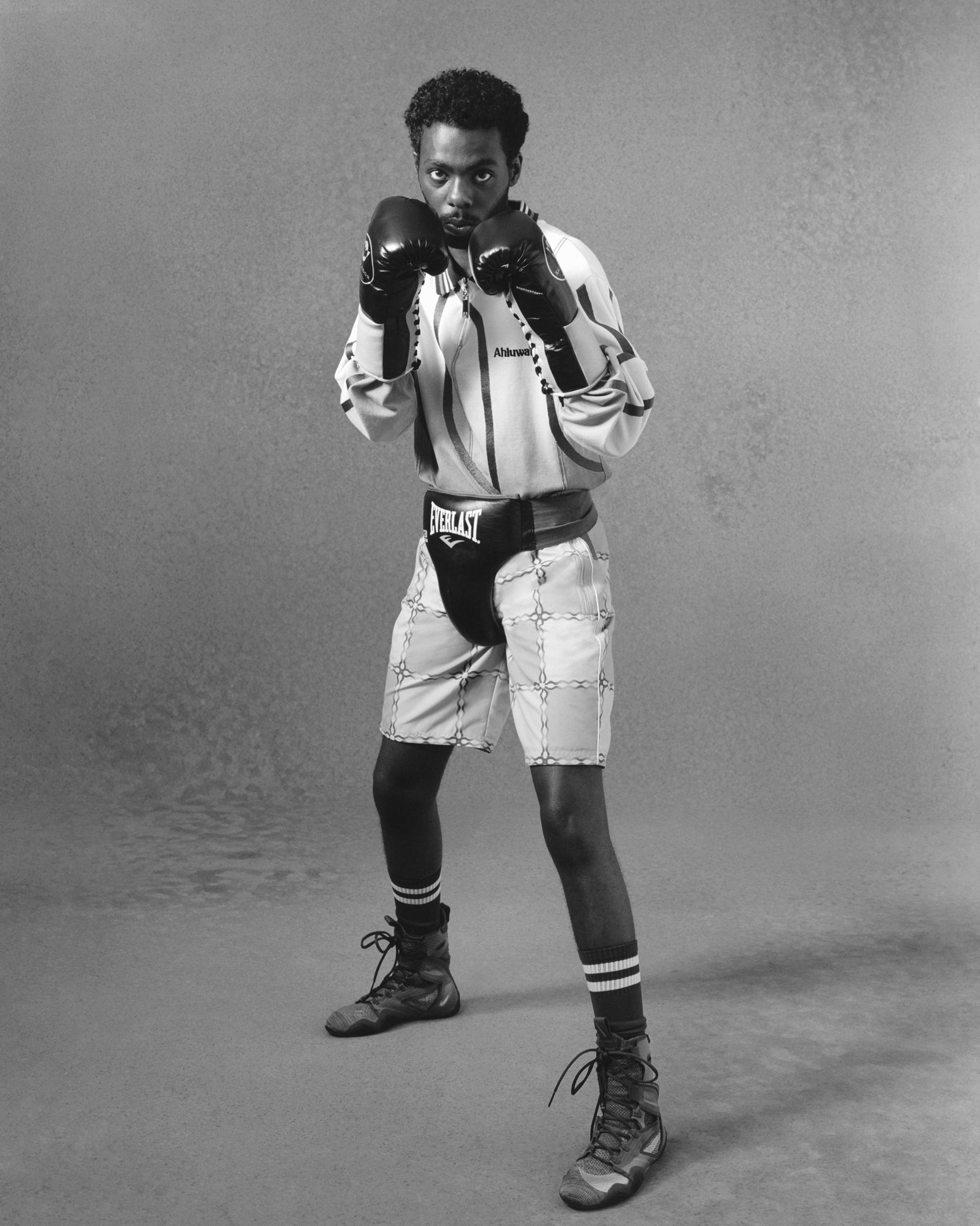

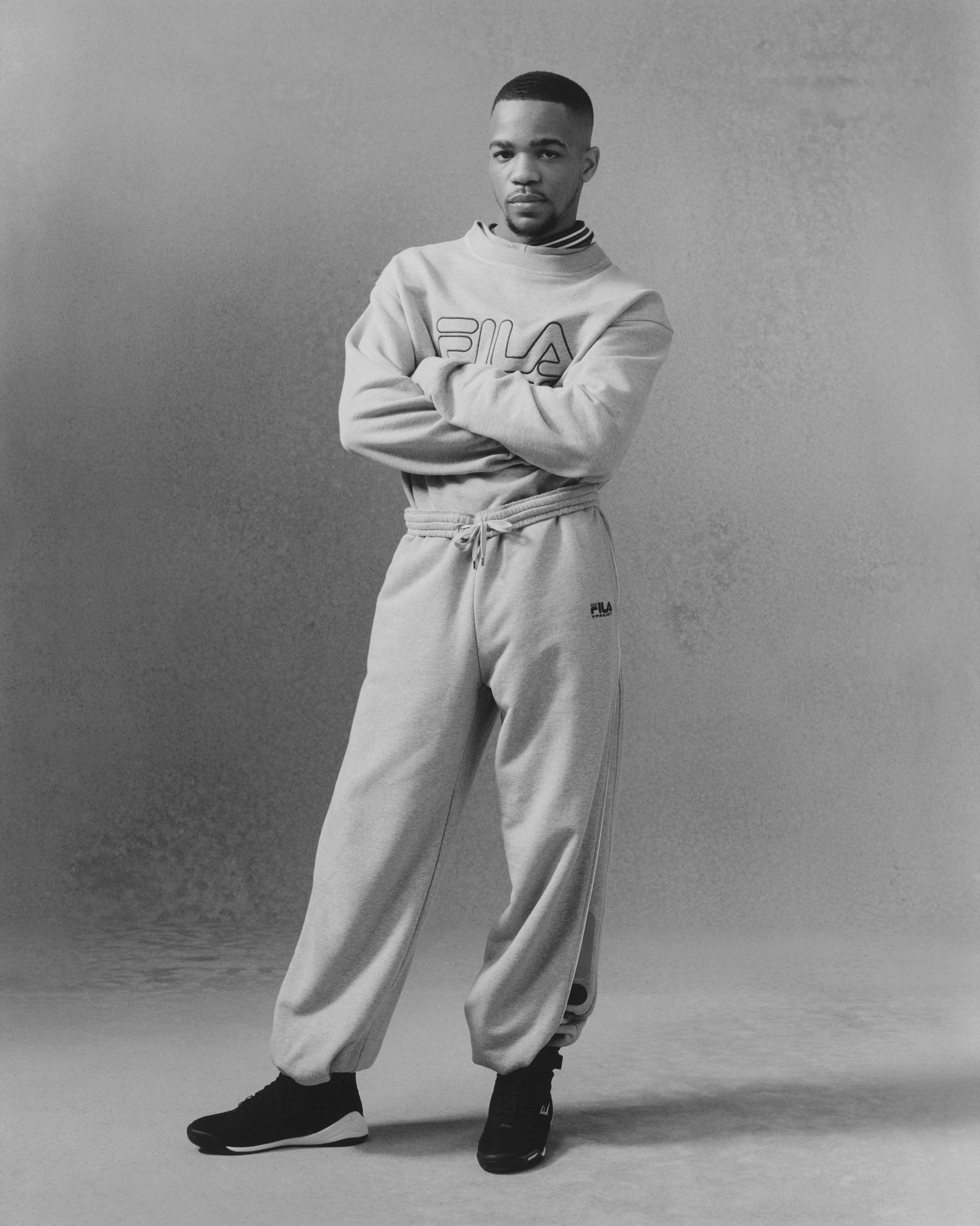

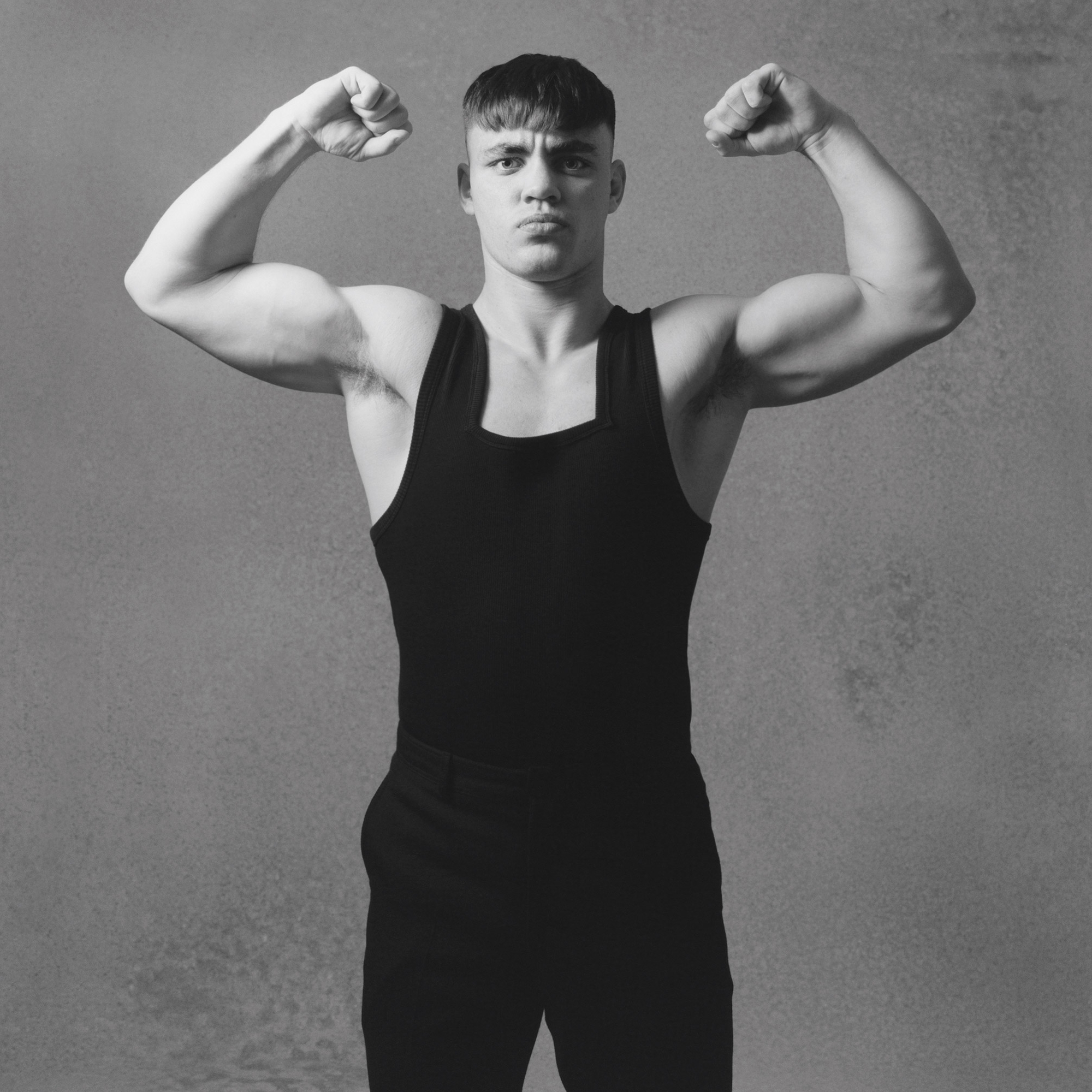

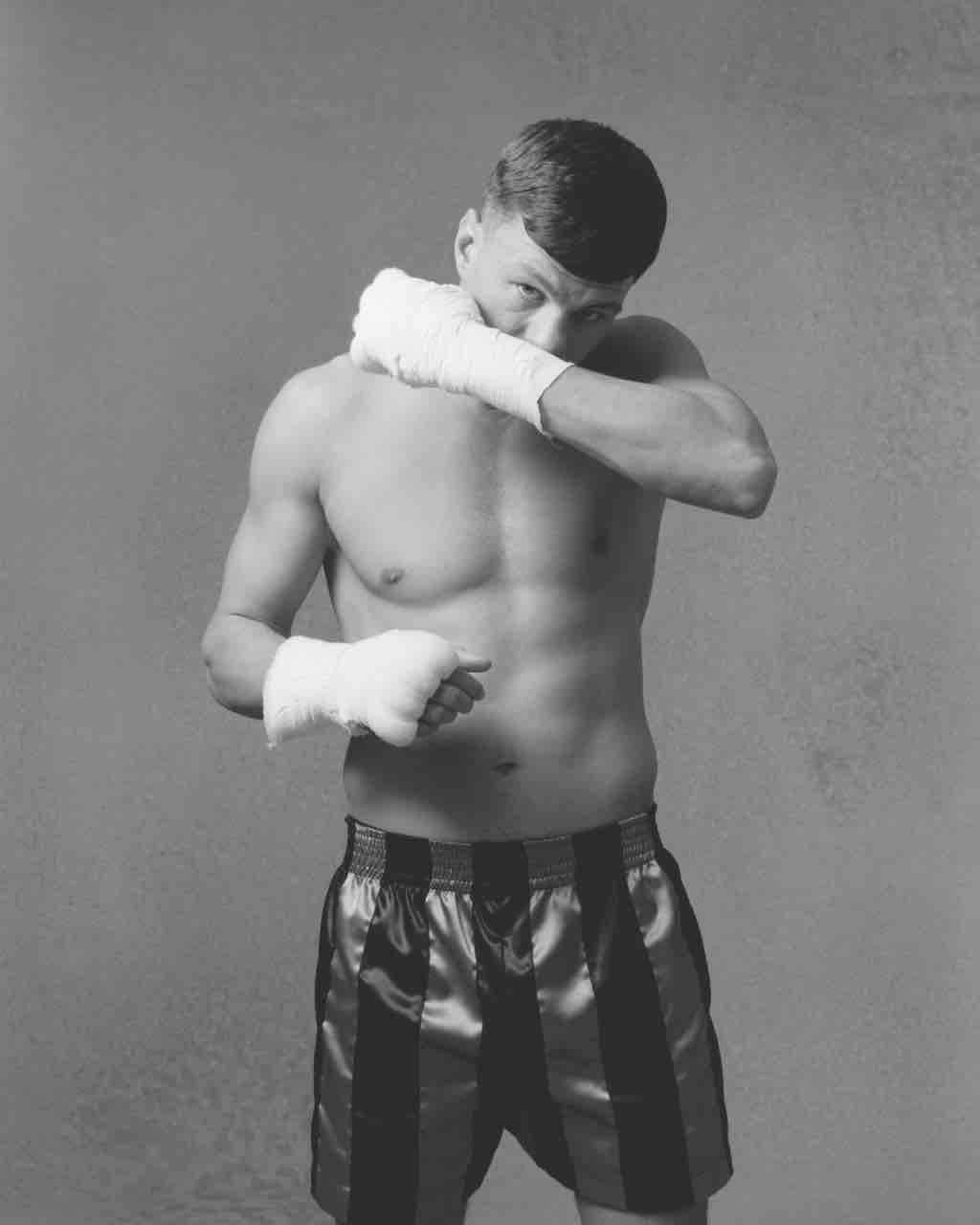

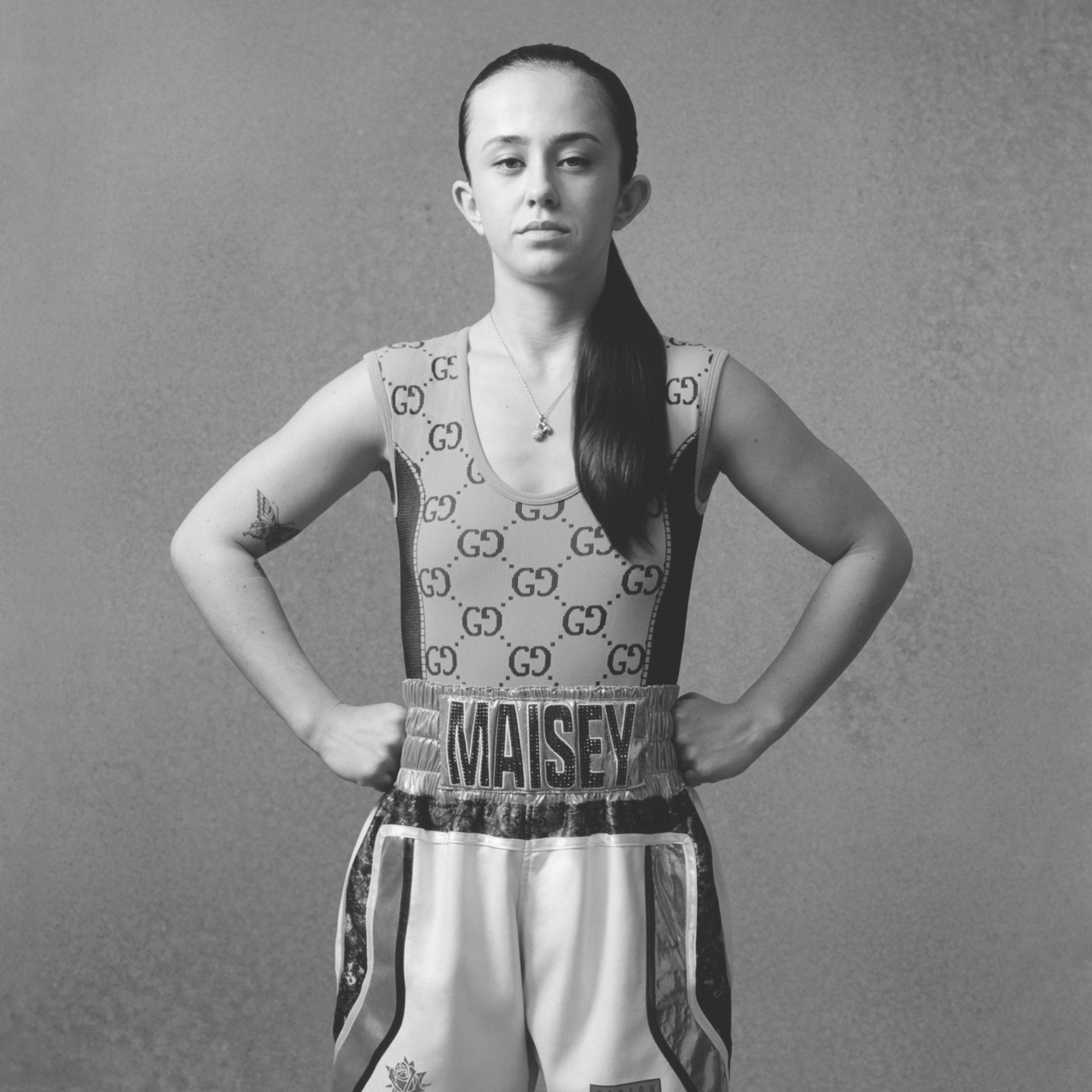

The images in this article are taken from our Issue 01 feature, PUNCH, by Ryan Pickard, Fumi Homma, and Stuart Williamson.

After Alexander Volkanovski lost his lightweight match to Islam Makhachev at UFC 284, you could be forgiven for thinking, judging from the reaction, that he had in fact won. Yes, he had just moved up from featherweight, and yes, it was still fairly even throughout – but ultimately, Makachev pretty convincingly ground out the win via his usual method of death by wrestling, despite being outlanded on overall strikes by 164 to 95.

“If you saw UFC 284’s main event and came away anything less than amazed by the talents of the featherweight king, I question whether you know what you’re watching”, gushed MMA Fighting after the fight. “Volk lost nothing tonight. He fought better than anyone thought he could. He is as good as anyone at any weight in the world”, added UFC heavyweight champ Daniel Cormier.

Compare that to the way people reacted to Anthony Joshua’s loss to Andy Ruiz.

“In my opinion Anthony Joshua has peaked and has kind of exposed himself. He’ll never be the same. The heart has shifted. He has been and still is an imposing guy, but again I feel will not ever have [the] same impact”, tweeted boxing writer James Smith. “What a damn disgrace. Joshua looked completely gassed! More fatigued than hurt! Now how in the hell did you let that happen?”, asked an exasperated Stephen A. Smith, the ESPN pundit.

Yes, the context was very different: a brave attempt at moving up a weight between two fighters at the top of the pound for pound tree, compared to a shock defeat by a last minute replacement. But the glee with which the media began to pick apart Joshua after his first loss, compared to the way in which pundits began and continue to venerate Volkanovski after his first loss, speaks to a strange mentality present in boxing that just isn’t in many, if any, other sports – let alone combat sports; particularly in the UK, but also in America too.

The weird disdain people had for Amir Khan, the multiple-times world champion. The quiet hostility people have for Joshua, easily one of the biggest draws of heavyweight boxing in the last decade. The way in which fighters like Daniel Dubois, Billy Joe Saunders, James DeGale, or even Ricky Hatton and David Haye were seen as lesser by fans, promoters, and the media after their first defeats, even though they were pushing themselves against often world class opposition.

Carl Froch, in perhaps the perfect recent example of how fickle British boxing punditry can be, said, “Where does he go from here? That could be curtains on his career”, after Chris Eubank Jr. lost his fight to Liam Smith, only for him to say of Liam Smith, “For me, his career is over”, when he lost the rematch.

Over on YouTube, you only have to type in ‘boxer’s first loss’ to see plenty of videos, all gaudily showing big fighters going through their first defeat. Often it’s revelling in the downfall of fighters who are seen as more cocky, like Adrien Broner or Prince Naseem Hamed, which you can understand in some context. People like it when showy people are taken down a few notches: it feels karmic, natural, allowed – encouraged even.

Perhaps it’s a knock-on effect of the red top celebrity culture we’ve allowed to permeate throughout our society, where a string of media organisations can hold the sword of Damocles over any and every celebrity’s head. Perhaps it’s that we’re living in a social media world, where with every loss you become ‘washed’; where only the most negative comments get celebrated by the algorithmic engagement machine; where punditry thrives off being as infuriating as possible in the name of ‘honest opinion’.

When you’ve got the full force of a top promotional team behind you and Sky Sports gushing over you demolishing tomato cans, the world is your oyster as a prospect. But one crushing loss later, your promotional team drops you, you get relegated to Channel 5, and suddenly you’re a journeyman. And from there on out it’s an arduous uphill slog to get yourself back to anywhere near contention for any titles.

Perhaps generational fighters like Joe Calzaghe or Floyd Mayweather have skewered our expectations of what a fighter’s career should look like. But – and this isn’t aimed at either of those fighters, who I think were both just genuinely exceptional – the reason a lot of modern boxers often look so great until they lose their first fight is because they have padded their records.

People say Mayweather never fought the best during his prime, but even if you take the Manny Pacquiao fight – one that people often cite as something he ducked until Pacman was past his best – it took place in 2015, a full six years before Manny retired, and a full six years of him fighting at the highest level at welterweight, during which time he won three world titles.

Compare that to someone like Tyson Fury who, despite being probably more talented than any heavyweight boxer currently around (with the possible exception of Oleksandr Usyk, who Fury seems intent on avoiding), has kept his 0 by padding out his record with unnecessary trilogies against Chisora and Wilder, Jake Paul-esque fights with MMA brawlers like Francis Ngannou, or bouts with journeymen like Schwarz and Wallin. Fury might well be the best heavyweight of this generation, but Joshua for me has had a far better career than him even with those three losses on his record, because he’s always fought the best he could possibly find. Yes, he was outclassed by Usyk twice, but even from the first to the second fight you could see how much he had improved; how much he had developed as a technical boxer – a personal development which is what losses should be all about for any fighter.

“I don’t take it as a defeat, I take it as a big learning curve in my career,” said Saul ‘Canelo’ Alvarez of his first loss, to Mayweather. Speaking to DAZN, Canelo went on: “The biggest lesson I learned was that I didn’t want to feel what you feel when you lose.”

He’s since gone on from that fight to be a mainstay in the pound for pound top 10, essentially lapping the middleweight divisions in terms of belts won and challengers beaten, and will almost certainly go down in history as one of the greatest fighters of all time.

Outside of boxing, it’s almost impossible to think of any fighters who are considered the best in their current disciplines that have gone undefeated. Saenchai, probably the greatest living Muay Thai fighter, has lost 49 times. Gordon Ryan, one of the most dominant jujutsu practitioners of all time, has lost nine times. I can only think of Khabib Nurmagomedov as someone outside of boxing who consistently fought at the highest level in his discipline and still managed to retire with a perfect record (29-0 in MMA) – and even then it was because he retired far too early, at 29, due to personal reasons.

If you ignored his history of steroid taking, no contests and dubious disqualifications (which, to be fair, a lot of people do), you could also make the same argument for Jon Jones. In my eyes, no one has (or will) actually beaten him fair and square in the cage, although it is of course debatable whether he would’ve beaten Daniel Cormier in their UFC 214 fight had he not taken steroids (for what it’s worth I think he definitely would have).

Liam Harrison, who is widely considered the most influential British Muay Thai fighter ever, said of his first TKO defeat: “My first time I got stopped against Anuwat [Kaewsamrit], I think that was the best thing that ever happened to me because it made me change my total, my mindset and everything. It made my mindset more bulletproof, and then I came back”. He went on to explain: “If I wouldn’t have lost that fight the way I did, I probably wouldn’t have got the rematch. That was probably one of the biggest wins for a UK fighter in history – for me to beat Anuwat.”

This, for me, is what losing is all about. When I lost my first MMA fight earlier this year by a first round submission, I was at the time pretty devastated. Months of training, a rigorous diet, and constant injuries had made me believe that I was almost entitled to a win. A strange thought, but one you often get when swilling over something mentally and physically for such a long time. In retrospect I realise now that my ground game was woefully undercooked, and so I have been relentlessly focusing on it ever since. I’m still not happy with the loss – no one ever is – but it’s something I needed to go through to realise how and why I should get better.

Similarly, a boxer can be more exciting as an athlete; as a spectacle, after a loss. Canelo’s defence improved hugely after losing to Floyd. Muhammed Ali became the most exciting heavyweight of all time after his loss to Joe Frazier. Amir Khan was involved in some incredible fights after his first loss to Breidis Prescott, headlining shows in some of America’s top venues.

And, without wanting to sound too mawkish, losing is a vital part of what it means to be human. It’s a reminder of our own imperfections, but also of our ability to grow, adapt and evolve. Ultimately, you learn who you really are after a loss. Are you the kind of person that will just give up? Or are you the kind of person that will use a loss as inspiration to progress? Like Sylvester Stallone famously barks in his most famous role, as the barely intelligible imaginary boxer Rocky Balboa: “Life isn’t about how hard you can hit, it’s about how hard you can get hit, and keep moving forward… that’s how winning is done”. And if it’s a good enough philosophy for Rocky, it’s good enough for me.