RD

You grew up in Columbus; what was your childhood like? Were you always taking photographs? Was photography something that always spoke to you as an art form?

GW

The camera has always been a tool, primarily because my mother actually teaches art and photography. So cameras were around the house, most of them dysfunctional, but they were there, collecting dust, and when I was a kid I would play with them. But it wasn’t until probably my high-school years that I started thinking of it as a viable tool for representation. And then in college, when I was studying the history of photography, I started really leaning into my own photographic practice. I think I got most excited when I started learning about other photographers and different ways of seeing things, different ways of thinking about framing. I started thinking, ‘Oh, shit. What’s inside of my frame? What’s outside of my frame?’

RD

I’ve read that your work comes out of a place of documentary and going on the street and photographing people that you see; since you’ve moved to Venice Beach in Los Angeles, can you speak about your interest in capturing real life?

GW

The camera has always been an intermediary tool for me to negotiate space and think about representation and what it means to weave, if you will, the fabric of a place. And it’s good for me in terms of my own personal mapping. For me, any time I’ve landed in a place for any period of time, I start mapping the space. I think of the map as a set of shifting borders and boundaries and perspectives. I think of mapping my neighbourhood in Venice Beach as a series of intersections of multiple perspectives. So depending on the angle with which you view a moment, when you view some kind of exchange, you decide to be present and acknowledge your neighbour, to see and be seen. That’s what makes up the fabric of ‘neighbourhood’, in my opinion. I’ve noticed that over time, you discern the connections and intersections throughout a neighbourhood that make that fabric that we can all actually participate in, knowing that nothing is truly fixed – except for sidewalk, concrete and metal and things that you can skin your knee on!

RD

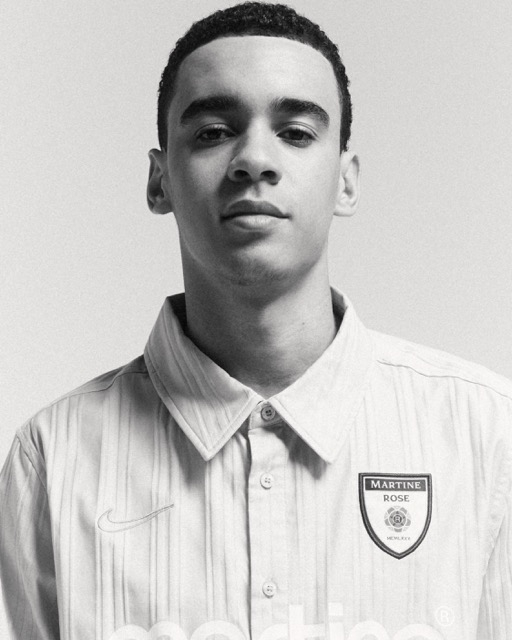

That’s something that I really see in your work. You create installations incorporating steel gates and fences, and then you weave through the chain-link mesh an actual printed photograph. Often you’re presenting the viewer with portraits of black bodies in space, but primarily exterior environments, like beaches or sunsets; or you see sportspeople playing games or hanging out in the neighbourhood. Can you tell me about the importance of the exterior and of natural light within the work?

GW

I’m very affected by light. I’m very seduced by light in that same way of exploring any place that I find myself in. It’s often about where the light is, particularly in places near to bodies of water, like where I live in Venice Beach. The elements – light, water, air – all these things are things that we all are. It’s almost like a book. We all get to read it and we all get to formulate our own relationship to it, to those elements. Personally, I love the water. I love to go into the ocean, even just to take a dip. If I’m angry, I go to the water, get in, shift all the ions. But the way in which it forces you to be present is something that I also find in the moments that I photograph. There is an unspoken communication that often happens when I’m dealing with people on the street, which is always a negotiation, because they see me. I’m a black man with a camera. It’s not just a camera floating around, it’s a body, it’s a vibration, it’s an aura.

RD

Some of your works have extraordinary titles. One of my favourite works by you is called Astral Traveling Like Alter Ether Rhythms On Sunday Breezes from 2021. It’s this amazing image of a young black kid running into a wave, and there is something so joyous. It’s what you’re talking about. I’m really interested in this idea of transformation.

GW

Sometimes it’s just the exchange of energy that is the thing. There’s a piece called Notice of Intent, and it’s two men playing speed-chess, and I sat and documented, I just zoomed in real nice and tight on the board itself and watched the whole game unfold. So hands kept coming into the frame in this constant choreography, and the black knight is sitting here and the bishop over here, right? It was this rapid-fire negotiation between these two guys. I realised it was all about negotiation. Notice of Intent: that title comes from the Department of Planning – notice of demolition, notice of intent. And honestly, what I always think when I see those signs, there’s a block-letter headline, NOTICE OF INTENT, and then there’s all of this language below it and it becomes very complex. And it’s almost like, ‘Don’t notice the intent’. It’s a strange irony, but I liked it as a metaphor. The chess game in the park, the movement and negotiation of the pieces: I was thinking about that in terms of the whole neighbourhood. These guys would be the OGs in our neighbourhood, and they were kind enough to let me photograph them playing this game.

RD

I think that’s what’s so powerful about your work, there’s an incredible sense of dignity and a positive energy. I think there’s so much trauma and sadness and anger – to see art bringing thoughts of dignity or joy or solidarity within a community, there’s something so special about that. And I think that’s why your work is so precious to me.