Weightless. Flying through the air. Twisting and tumbling at breakneck speed. To watch cheerleading routines is an experience both thrilling and oddly soothing – because, certainly in the videos posted to social media, these young women (they typically are young women) always make the shot. Tumbling in the air, they land – on one white sneaker, on a palm of a male partner’s outstretched hand – with a smile of perfect white teeth.

Or, even more jaw-dropping, there’s the pyramid. A group effort of epic proportions, involving 10 athletes, each performing their role to perfection, with a kind of effortlessness and grace more associated with something like ballet than an Olympic sport.

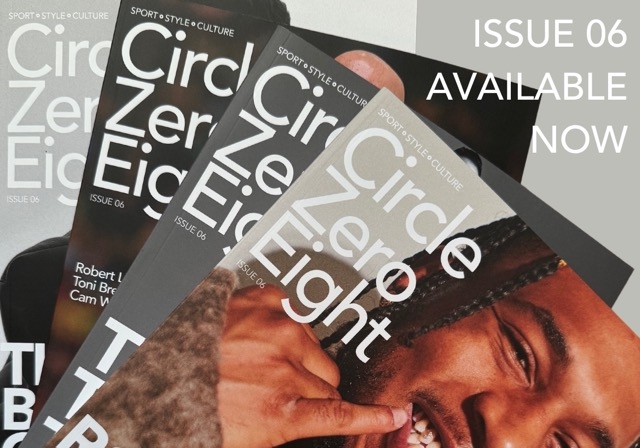

Our young athletes here – part of the junior cheer squad at San Marin High School in California – show the best of cheer. They look every inch the perfect cheerleaders, with their pom-poms, their varsity uniforms and grins. Of course, as anyone involved in the cheerleading community knows, there is blood, sweat and tears behind those winning smiles.

Some of the rest of us know this too now. We went behind the curtain with Netflix series Cheer, a heartwarming documentary about the cheer team at Navarro college in Texas. Presided over by tough but fair coach Monica Aldama, we watched the likes of Gabi, Lexi, La’Darius and Jerry learn to tumble and to lift, with gruelling repetition en route to perfecting routines for the big prize: winning the Daytona championships. Sore ribs, tweaked ankles, dislocated elbows and physio tape were par for the course. And cheer is about far more than athletics, it turns out. The cheer squad as a community – a kind of chosen family – was revealed, a safe space for those, like La’Darius and Lexi, who had tough starts in life.

This combination of breathtaking skills and moving stories made the first series of Cheer, released in January 2020, a lockdown 1 boxset hit, and arguably put the world of cheerleading on the global radar, beyond the US where it’s central to culture.

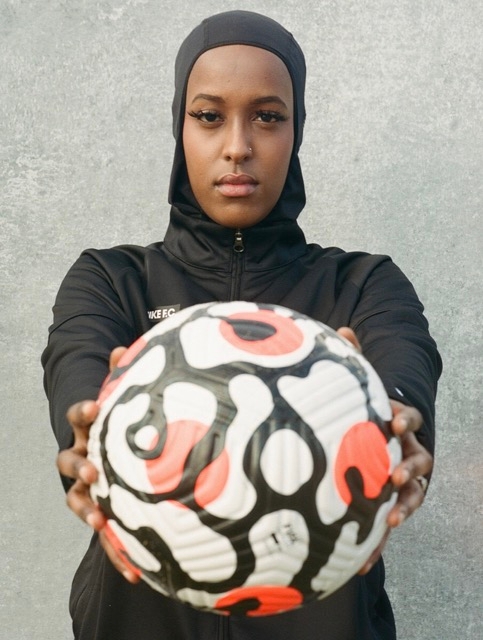

Two years and another series later, and cheerleading has gone beyond Cheer. In July 2021, it was officially recognised as an Olympic sport by the IOC, meaning it could be included in upcoming tournaments (it’s thought the earliest this could happen is Los Angeles 2028). This news might be seen as part of a wider recognition of the athleticism and skill of activities sometimes greeted with ‘that’s not a sport’ bluster from traditionalists. It follows the addition of skateboarding and surfing to Tokyo 2020 last year, and breaking (as in breakdancing) arriving in the programme for 2024. Compared to these sports, cheerleading is less cool and more glamorous; it will join gymnastics and ice skating as Olympic sports that put emphasis on sequins and sparkles as well as tricks and somersaults. A can of hairspray remains an essential item. If the look is different, cheerleading does have a lot in common with these other new additions. Like skateboarding, surfing and breaking – which have roots in street culture, rather than a sports field – it has been the victim of discrimination. Since it’s mostly associated with women, good old-fashioned sexism has dominated the thinking. Cheerleading was dismissed as something pretty, but also something that happens on the sidelines.

In actual fact, cheerleading is a massive industry – one that, as Cheer demonstrated, appeals widely to young men and women. In 2017, 3.82m people aged six or over participated in cheerleading in the US, with 100m households tuning into the Daytona final. The industry was thought to be worth around $2b in 2020, with an all-star cheerleader (the type on Aldama’s radar) paying around $4,000 in competition fees and costumes for a year. While, comparatively, the world of cheer is tiny in the UK by comparison (an estimated 89,000 people were involved in 2020), it’s growing. Team England even won gold in the World Championship in 2017.

As the name suggests, cheerleading did start from the sidelines. It developed as a way to cheer on the athletes on the field. Even if it is now seen as a fundamentally female sport, the original participants were men – and that was the case until relatively recently. Developing in tandem with American football in all-male Ivy League colleges from the 1880s onwards, cheerleaders were kind of hype men for home crowds watching the games – they were sometimes even called ‘yell leaders’.

Women began to join cheer squads as colleges became co-ed in the 20s and 30s. It was during the Second World War – when college-age men were recruited to the army – that the baton passed to women. High schools introduced cheer squads. By the 70s, around 95% of cheerleaders were women, and they were sex symbols. The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders – who, in 1971, switched from the cheerleader skirts to hotpants – became the ideal, with dance routines, rather than actual cheers, the norm. By the 80s, on the sidelines during halftime shows for NFL games, they were, for some, perfect examples of wholesome all-American glamour. For others, they were a very visible example of women being objectified for male entertainment.

There are fewer cheerleaders at NFL games now. Some football teams, including the Los Angeles Rams, have men in their cheerleading squads, but the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders remain, and sex appeal is central to their schtick – they have swimsuit calendars every year. The debate over gratuitous eye candy versus all-American fun rages on.

Because, while things like Cheer and the Olympic recognition show a shift in the place of cheerleading in culture, the cheerleader remains, by and large, a fantasy of femininity, typically in a short pleated skirt accessorised with pom-poms, a ponytail and that winning smile – one that is always, it almost goes without saying, young, blonde, female and white. She is a hot girl archetype – the popular girl, the alpha, the one who dates the quarterback. This means the cheerleader’s place in popular culture is endlessly played with. See Maddy and Cassie in Euphoria, in cheerleading uniforms and directional eye makeup. See Olivia Rodrigo in the ‘Good For U’ video, all PVC gloves and riot grrl energy. See a rare cheerleader of colour, Gabrielle Union, as Isis, in the much-loved Bring It On. See – my favourite – the oldest cheerleader ever, Nadine in Twin Peaks.

Competitive cheerleading – the kind that requires skill, fearlessness and power – is a way for this world to fight back against these stereotypes and clichés – to speak up. Cheer is a showcase for the skill and dedication in the sport, its community and diversity. Put simply, to be a contender here requires way more than mastery of some pom poms, and a blonde ponytail.

It’s this side of cheerleading that our young athletes in San Marin no doubt emulate. Because, as much as they might be carrying an injury and their bones ache, that one time out of 30 when they complete the trick, when the pyramid is perfect, is worth all the pain. Put like that, it’s no wonder the smiles are winning.