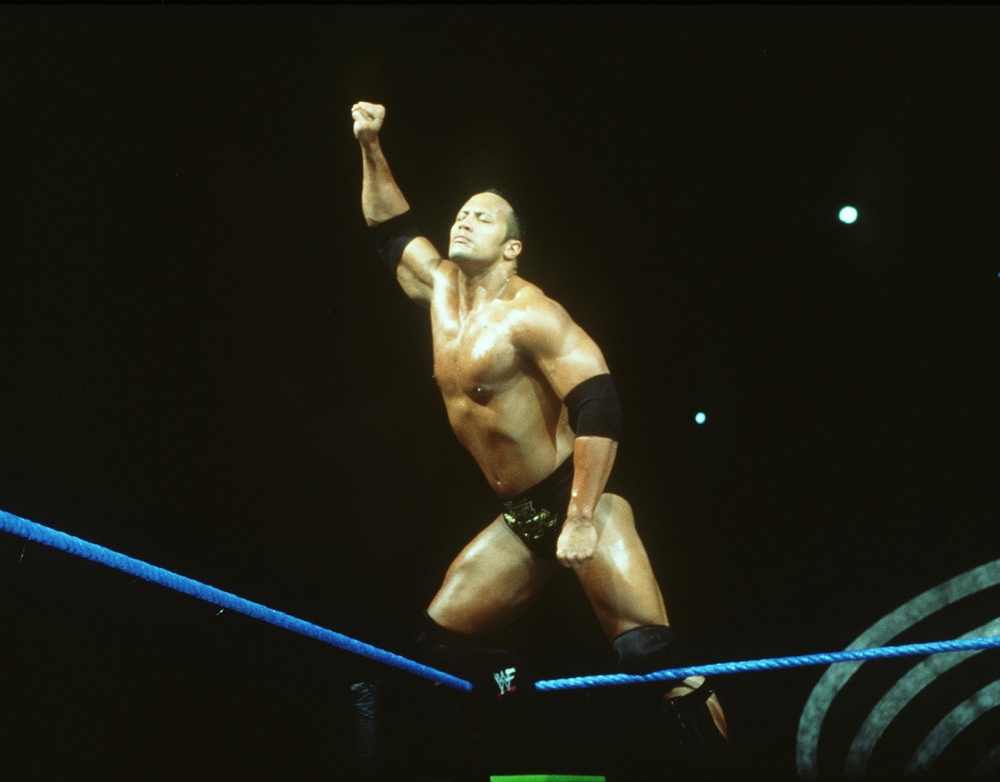

Photographer: Marouane Beslem

Photographer: Joseph Ouechen

Photographer: Marouane Beslem

Photographer: Joseph Ouechen

Photographer: Marouane Beslem

Photographer: Jinane Ennasri

Photographer: Jinane Ennasri

Photographer: Achraf Zamane

Photographer: Achraf Zamane

Photographer: Inès Bouallou

Photographer: Inès Bouallou

Photographer: Joseph Ouechen

Moroccan football is having a bit of a moment. And that’s putting it lightly.

From the men’s team reaching the semi-finals of the 2022 World Cup – the first Muslim majority country to do so – to the women’s team following up with their own historic run in the 2023 iteration, it’s fair to say they’re doing alright. And now the country can look forward to hosting the next Women’s African Cup of Nations (WAFCON) in 2024; the Men’s AFCON in 2025; before co-hosting the 2030 Men’s World Cup alongside Spain and Portugal.

It’s a good time to be a Moroccan footie fan. And almost every Moroccan is.

Photographer: Marouane Beslem

“As we both know, football is like a second language in Morocco”, Jinane Ennasri reminds me when I ask her what motivates her to photograph the country’s football culture. Quite simply, documenting Morocco means documenting football.

But over the last few years that language, and what it says, has evolved.

“Football in Morocco is the only outlet for young people”, Achraf Zamane, a young photographer from Casablanca and avid collector of vintage shirts, asserts. Football is an “endless roar” – a free outlet for many with little access to other entertainment.

2021 was the first year I visited Morocco. I’d be lying if I said I was motivated by a deep desire to understand North African football culture: flights were five euros and I’m impulsive – sue me. When borders closed due to COVID a few days later, I stuck around.

Photographer: Joseph Ouechen

The Arab Cup was on at the time, and one evening, after a long battle with friends who argued it maybe wasn’t the best idea for me to come (‘no, you are crazy British girl’ and ‘you will die’ being just two reasons), I ended up in what can only be described as a North African dive bar watching Morocco vs. Algeria.

Now, for those not absorbed in geopolitical tensions in the region, it’s something of an understatement to say that relations between the neighbours are frosty. When a Senegalese man appeared to smirk as Algeria scored a penalty in the 62 minute, he was thrown across the room and accused of being an Algeria supporter by a particularly irate Moroccan. Chaos ensued; glasses smashed across the floor – almost nobody noticed the equaliser just two minutes later.

When they did, the situation calmed and the men enjoyed a bottle of rosé together as if nothing had happened.

Photographer: Marouane Beslem

That match ended in a loss for Morocco (5-3 on penalties), but as my first experience of the local football culture, it left a lasting impression. Sure, there was passion, but the game was also embedded into, or threaded through, political conflicts.

In the local league, chants in the stadiums frequently take aim at government failure and inequality. This is especially the case for Raja Club Athletic fans, a team based in Casablanca with deep working-class roots. Campaigns amongst the Ultras against violence and sexism may have softened the more sensational elements, but the political drive remains. In Morocco, football is a statement of identity in all its guises: political, regional, economic.

“Here in Casablanca”, street photographer Joseph Ouechen tells me, “we used to only see Wydad or Raja jerseys, but now it’s eclectic – you see people wearing the jerseys of the whole country from north to south, people who migrate for work are reclaiming their identities on the streets”.

Photographer: Joseph Ouechen

Ouechen’s work looks at how fashion across Morocco reflects the particularities of modernity there. Football jerseys are part of that, marking migration patterns across the country as people move for work and opportunities. And internationally – as Ouechen’s images of Senegalese supporters celebrating their team’s success in Casablanca show.

Zamane has been collecting vintage shirts for years; styling and shooting them and asserting their place within fashion by doing so. His work portrays the culture and style of the more deprived areas of Casablanca: “The photos in the living room, the terrace, or in the mazes of the slums are important, because I express the love and passion that we feel for football in these difficult neighbourhoods. Football in these environments is not just a simple game, it is a real escape”.

“In the past, a Berber from southern Morocco might wear traditional dress”, Ouechen adds. “But now he wears his local jersey – it’s a new way of showing identity”. Just like other fashion, football shirts are a means of self-expression, often verging on socio-political statements, but it’s only recently that this is being properly understood. Previously they were simply an indicator of someone being of lower status and dismissed as fanaticism.

Photographer: Marouane Beslem

In 2022, these ideas started to change. Morocco landed firmly in the international football psyche with a win against Belgium’s ‘golden generation’ in the group stages of the World Cup. Overnight, Moroccan football was in the global spotlight.

“I would see videos coming out of Morocco where people were hysterical”, recalls Ennasri, who was in the US at the time. “The streets were full – you would think that we’d won the whole World Cup”.

I was in the country, watching in a tiny village where donkeys pass through more frequently than cars. As far as I know, there’s one TV screen there. It’s found in the local shop – although ‘shop’ should be understood as an unmarked door, on a backstreet, leading into a small dark room where a man waits behind a gap in the wall to tell you if he has whatever it is you request.

This wasn’t Marrakech. And it certainly wasn’t Casablanca. But still, the atmosphere was contagious. Half the village piled into the dingy room to watch the matches. They’d sit on old Coke crates and spill out onto the streets. It cracked them up that I was there with them, but they wouldn’t accept me standing in the doorway – I had to have a good crate and an unobstructed view.

Photographer: Jinane Ennasri

“The World Cup”, Ouechen reflects, “showed a country that was open and rich, but still deep in tradition. And that’s even though at the time there was lots of questioning – are we an African team, are we an Arab team? It doesn’t matter – we’re a diverse country; we all feel connected to the team”.

Seeing Morocco on the world stage helped forge a sense of national pride and identity that embraced that diversity. From Amazigh villages to the global diaspora, footballing success evoked a collective identity.

Ennasri echoes these thoughts. In her view, a large part of the team’s success came from the fact that the country believed in itself – “for once!” she adds. “We didn’t look at our neighbours, we didn’t look for European acceptance”.

And that extended to the players. In previous years I’d heard plenty from Moroccan friends about how French- or Belgian-Moroccans who played in European leagues were traitors, or not really Moroccan. So seeing the wholehearted acceptance of European-Moroccan players – and even the coach, Walid Regragui – in the World Cup was a shock.

Photographer: Jinane Ennasri

Ouechen elaborates on this phenomenon: “I’m not going to say it’s not our team because some people grew up in Europe. They are European, they speak many languages – but they are also Moroccans and that makes us proud”.

Pinpointing what led to that change of heart is tough, but in Ennasri’s view, “At the end of the day, they chose. The fact they chose Morocco excited us, but it also gave us hope”.

And so, wearing the national shirt increasingly represents an open, global Morocco.

Ouechen has seen this evolution firsthand as one of the first Moroccan fashion photographers to turn their camera towards the ‘popular’ (poorer) areas of Casablanca. “The last two years, I really started to notice it”, he says. “People outside these areas wear jerseys now; it’s becoming a trend – it’s something I never saw before”.

“Especially the Moroccan national team jersey”, he adds, before really driving the point home: “Even the rich people and the bobos [French slang for the bourgeois and bohemian] on Instagram and at fashion or arts events. That’s the biggest change, and it’s happened since the World Cup in Qatar”.

Photographer: Achraf Zamane

Even internationally, the shirt carries a new meaning. Morocco’s unexpected success against big European teams signified a change in football culture more broadly, people across the world celebrated their success as a marker of change. “Underdogs are always appreciated”, Marouane Beslem, another photographer, explains. “The way we defeated big teams? And us as a small African, Arab, Berber team? That was very inspiring for a lot of people”.

From where I was watching, it was palpable. There was pride, but also a celebration of victory against the status quo. Against Western dominance in football, sure, but also culturally, geopolitically.

Talking to some Senagalese migrants in Essaouira’s medina one afternoon before the semi-final they told me emphatically that they were looking forward to seeing France defeated.

But amongst all this rebellious spirit, one element remained disquieting. In the village, I was only ever amongst men.

Photographer: Achraf Zamane

It wasn’t at all that women weren’t watching. In fact, large screens were set up in city squares across the country to ensure a safe place for women and children. But women weren’t necessarily welcomed in other gathering spaces. Friends in Essaouira watching in cafes continually overheard pointed complaints about women ‘pretending’ to be interested and killing the vibe.

Yet those complaints didn’t stop many of the same individuals turning out to watch the women’s team’s campaign in the 2023 World Cup a few months later.

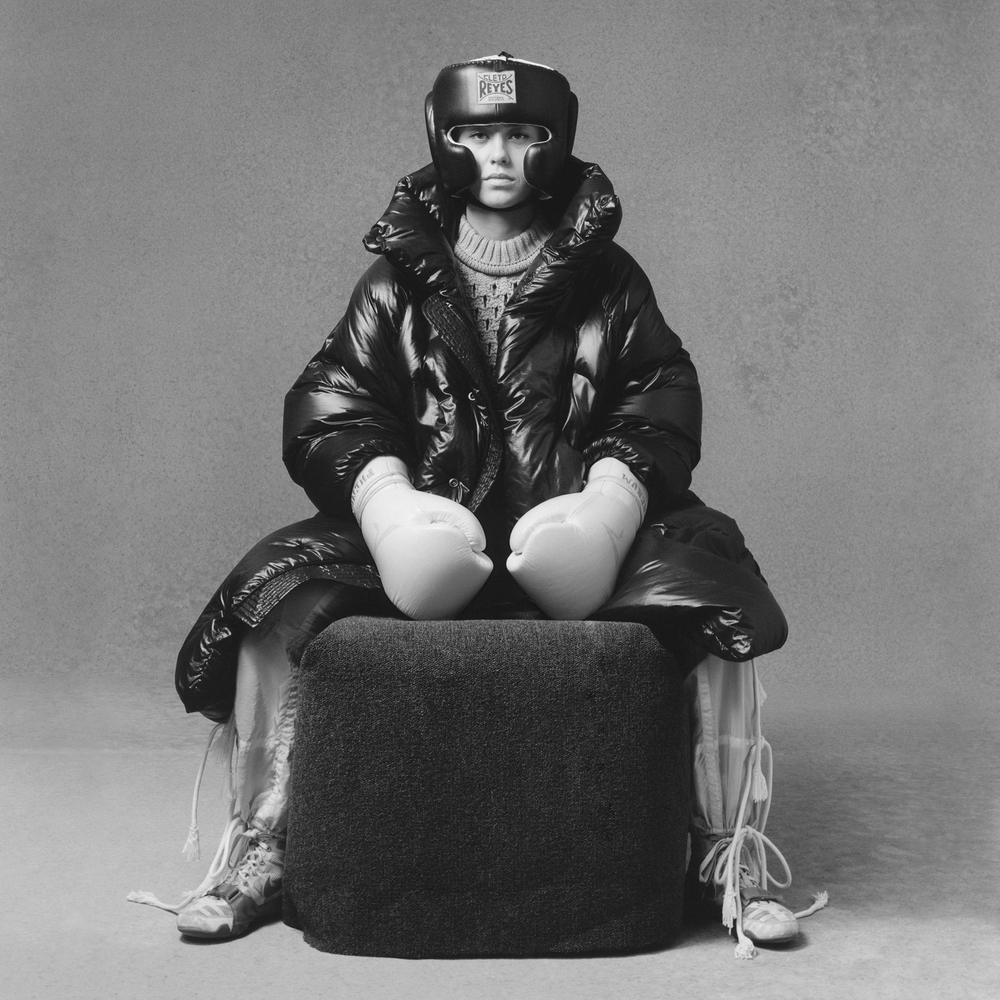

Although Inès Bouallou is now a photographer, her first ambition was to be a footballer. And she came close, training with AS Salé. At the time, though, “there was a lot of sexism; everyone was against me, except my mum”.

She explores these feelings in a series of self-portraits, images with a dreamlike quality showing her in a football shirt, ball in hand. There’s a melancholy to them – a frustration, perhaps, with the culture that surrounds the sport. In her images she’s able to remove the external world, to escape it, but she isn’t playing.

But change comes quickly. “It’s been 12 or 13 years since I was with Salé, so even in that time there’s been a change. Back then I was the only one playing, and the only one wearing the shirt – other than the guys”.

Photographer: Inès Bouallou

During the world cup Bouallou noticed a switch, especially in women asserting their right to public spaces surrounding football.

“Especially in cafes”, she interjects, “in some parts of Casablanca, and especially in Marrakech – you will find cafes with women – but it’s generally in the cities”. It’s not necessarily common, but it is evolving.

I asked Beslem if he noticed any differences between the two World Cups. “The vibes were very different”, he admits, adding that there were various reasons: the games were on very early; the players were less famous. He’s keen to point out that it’s not just Morocco, “it’s an issue everywhere in the world, there’s not as many eyes on women’s football”.

He also reminds me that during the Women’s African Cup of Nations, last held in Morocco, there were record attendances in the stadiums. These records will likely be beaten next year when the country hosts once more.

Photographer: Inès Bouallou

One of Ouechen’s images from the Women’s World Cup shows a man sitting in a blue café, watching the team celebrate. “That man”, he says, “was pretending that he had something in his eye, but he was crying. But because the café was crowded with men, he couldn’t show his emotion and he hid it instead”.

The irony was not lost on him. “It was funny, you know”, he reflects as we compare experiences. “I am there observing those men who were supportive of the girls, and yet at the same time, being harsh if they didn’t do well – returning to those old ideas of ‘your place is a kitchen; you could never score a goal’. They were constantly switching between these things”.

Ultimately, Morocco is a country of contrasts. It always has been, but in recent years football has really exposed these contrasts, as the culture surrounding the beautiful game changes and evolves. It will continue to do so, and for now it’s about sharing it because, as Ouechen concludes: “it’s crazy, but I believe in this Morocco; I want to show to other countries that it’s not black and white”.

Photographer: Joseph Ouechen