Corbin Shaw is a young British artist who originated from Sheffield, before moving to London to study at Central Saint Martins. Here, Shaw sits down with Robert Diament, co-host of TalkArt podcast and director of both the Carl Freedman Gallery and Counter Editions, to discuss his life, work, and influences, plus his new project on positive masculinity, made in collaboration with the students of Aylesbury Grammar School.

Robert Diament: I’ve been reading a lot about your work and your interest in masculinity and sport, can you talk a bit about your own experience of masculinity and how that’s rooted to where you grew up?

Corbin Shaw: It was at the forefront of growing up for me. It was something I was constantly thinking about and questioning, you know, does this make me happy? Do I agree with the sort of masculinity that I’m inheriting? It felt like this heavy load; this legacy of all the men that came before me, and how I can fill their hobnail boots. There’s such a history in Sheffield of industry, and a lot of those jobs don’t exist anymore. I grew up with my dad being a welder; going to work with him; going to the football with him; going to boxing –– I guess I was around a lot of men, even though at home I was with my three sisters and my mum, but then my dad would take me out to these masculine environments. His whole thing was always about toughening us up and getting us ready for the real world. It was like I was being shown loads of different masculine identities that I could embed myself in or try to aspire to. But a lot of the time I found myself quite alienated by it, although I was part of it. It felt to me like there was an expectation of men that was completely impossible for anyone to truly match up to, even the ones who are conforming so well in these environments. There’s something about competition that puts me off –– men wanting to beat each other makes me want to not get involved.

So then when I got to university, I was looking around at everyone else making autobiographical work and I thought to myself, “Oh God, I’ve never really questioned my own identity, would anyone really be interested in that?” But then when I started making work, I interviewed my dad and asked him about the way his dad had treated him growing up, and he was so confused as to why anyone would give a shit about northern men. So that’s really how I started; that’s what got me some attention whilst still at university, focusing on that. I think because when I first arrived there I was so confused about who I wanted to be, you know, I wanted to be ‘cool’. It was actually when I read Grayson Perry’s The Descent of Man that I think I found myself. It helped me to recognise myself and the men in my family, and I guess work out why I am like this or that. It’s a great book: it democratises a lot of information about gender performance in a way that I’d not considered before.

RD: I remember growing up, there was an expectation that boys will be boys, and girls will be girls in this really binary way, and competition was a big part of that –– especially for boys with sport. It’s so interesting that that had that effect on you.

CS: Yeah, I grew up playing football and boxing. Both were incredibly competitive, especially boxing, and when I think back to how scared I was –– I would shake before I had to get in the ring. Whereas now I run, so it allows me to be in competition just with myself; I set where the finish line is. When I was a kid I was so heavily policed by my dad on what was and wasn’t allowed. I always remember I used to get called up by my dad for wearing my mum’s slippers around the house; they were fluffy and had a little heel. I’ve always sat with my legs crossed too, and my dad would constantly ask, “Why do you do that?”, and I would say to him, “This is who I am; it’s how I feel comfortable”. But even small things like that made me conscious of myself. I think in some ways, my dad encouraged me to box because he felt like I was too feminine, and it was a reaction to that, like, “his masculinity is in crisis”. I think that can happen inside families, but also in society as a whole. As more attention and openness is being given to gender and things like trans rights, you then get this opposite reaction, with people like Andrew Tate coming up with opposing viewpoints. I feel like men are often the oppressor and the prisoner of their own gender, constantly policing themselves, whilst also policing other men. It feels like there’s this electric fence of homophobia: you don’t want to be seen doing or saying anything ‘wrong’, because there’ll be a man ready to say, “Well, that’s not how a bloke is supposed to be”.

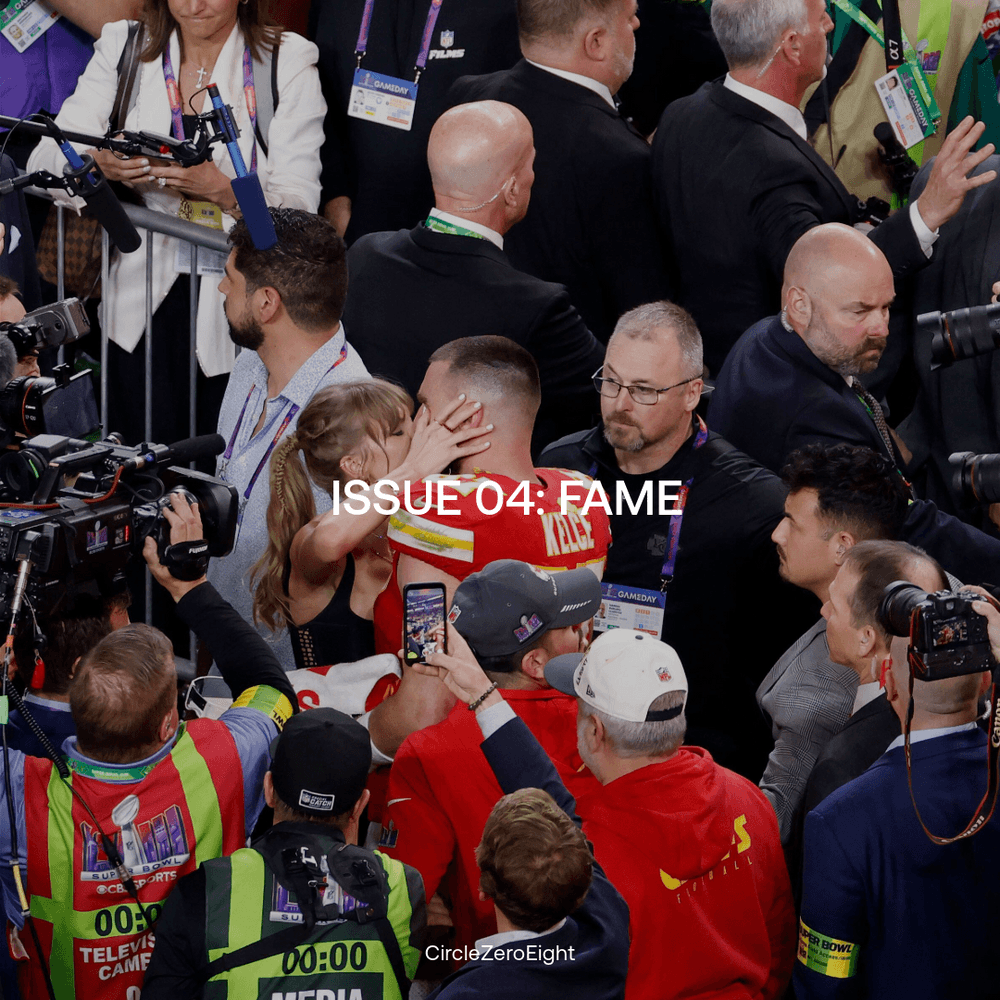

RD: I always find it so interesting that you see these images within sport that are highly charged, testosterone-filled moments between men, which could be perceived as homoerotic –– but that’s not how a lot of men perceive it.

CS: Yeah, like when a group of lads all kiss each other when England scores.

RD: Exactly! It’s like a way for men to allow themselves this kind of release, I’m not saying they want to be intimate with one another, but rather that it’s this opportunity to behave freely without fear of being judged. Which is a shame, because maybe if these things weren’t so heavily policed it might mean that men wouldn’t feel quite so hemmed in.

CS: I think there’s a tenderness and intimacy to male relationships that’s only allowed in specific contexts; like a man is ‘allowed’ to hug and kiss another man only when a goal is scored. Like with my dad: his dad never hugged or kissed him when he was growing up. He had to shake his hand before he went to bed, which meant that when me and my sisters were born he made the conscious decision to hug us and kiss us. So I think it’s about trying to break that cycle. For me with my work, I want to be a role model to young men, which is what was amazing about doing this project with the school. The kids were shocked at how young I am; that I looked like them; that I talked a bit like them; that I got their references. I think they thought I was going to be so out of touch.

RD: How old are you?

CS: I’m twenty-four. I always get it wrong. I told someone I was twenty-five the other day, but I’m definitely twenty-four!

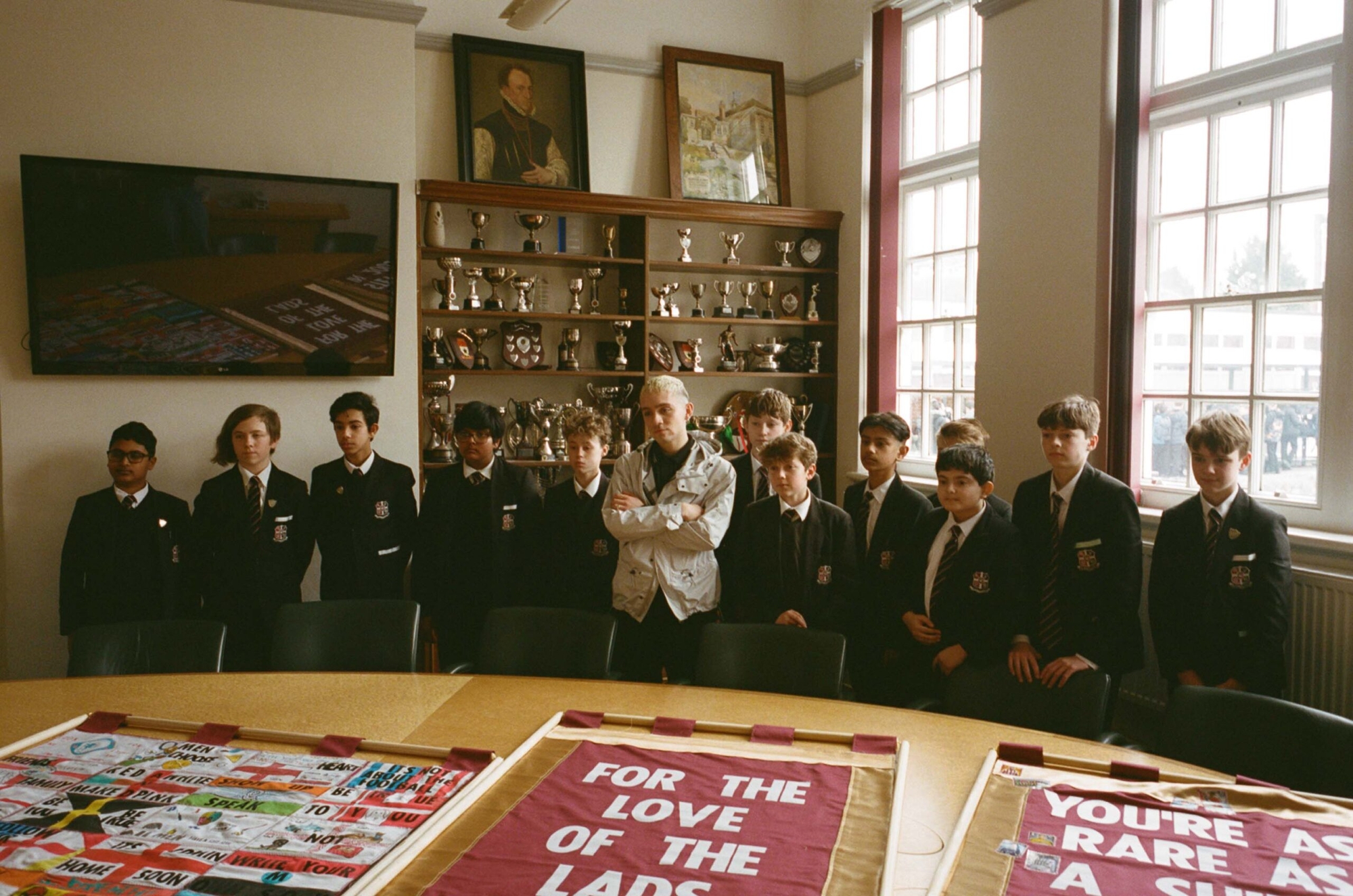

RD: Brilliant. Can you tell me a bit more about the project you mentioned? My understanding is that you went into a boys school, Aylesbury Grammar School, to inspire them and talk to them about your work. I think your best known works are the pieces you’ve done around the English flag, which you took to them and explained, and had them create their own flags in response. It must have been fascinating to see what they came up with.

CS: Yeah, it started with a talk with the Year 8 students (twelve and thirteen year olds) where I talked about attributes that we associate with masculinity – strength and bravery, for example – but how these can mean a lot of different things. Like bravery can be the ability to be vulnerable, or it could be if you’re brave enough to speak up when you hear another man being misogynistic or homophobic. The whole thing was so inspiring. I did the talk, and then we did a workshop where they designed their own flags on paper. I told them this story that my dad had told me, and it’s what inspired me to start making flags. A man from his town had committed suicide, and the other men of the town had made these flags in his honour –– I was really inspired by the way these men had used flags to subtly express themselves. It was just a really gorgeous way of communicating.

RD: Sort of like grieving through the artworks.

CS: Exactly, and it made me think about how flags in support are so often about segregation and hate for the opposite team. But what if they were about love? So the first flag I made said ‘We should talk about our feelings’, and I said to these boys, “What if your flag was a confession?” Then I showed them the second flag I’d made which said ‘Soften Up, Hard Lad’, which was a play on what my dad used to tell me when I’d do anything remotely feminine. These boys went straight into it, writing their thoughts down straight away with no outside influence. It was so incredible to see what they were thinking about, and quite shocking to see who inspires them; who they’re looking at; who the role models in their life are. But what was really interesting was that with a lot of them, their minds weren’t made up, which made it better in a way, because it meant they were in the perfect mindset to properly consider the question.

RD: Thirteen is such an important time. Looking at the works they made, there was one that says ‘Red and White Make Pink’, and I just love that. The way they constructed it as an artwork was really beautiful too.

CS: So that’s what we did with a smaller group after: we made these individual flags that I’m actually in the process of stitching together to make a big tapestry.

RD: Oh that sounds amazing, I can’t wait to see it.

CS: Yeah. I know it sounds silly, but it was so incredible because I don’t think I could have been that honest at that age. I was too worried about what people thought of me.

RD: There was one that refers to LGBT rights, with a country flag on it––

CS: The Malaysian flag.

RD: That’s it! And the Malaysian flag is peeling away and it says ‘Being Brave is Being Risky’, but they’ve crossed out ‘Risky’ and written ‘Your True Self’ with the LGBTQIA+ flag underneath –– it’s so brilliant to see.

CS: Honestly, they’re beautiful. There’s one with the Indian flag that says ‘Every flag has a soul’. With another one, the boy had never told anyone at school that his dad played the adult Billy Elliot at the end of the film. He wrote ‘Ballet is for men’ on his flag –– even none of the teachers knew the backstory.

RD: Wow!

CS: It was just amazing that we’d created this space where they all felt so comfortable and could say how they felt. One boy said to me, “What would your advice be –– everyone keeps telling me I need to get a girlfriend as quickly as possible”. It had become this place where they all wanted to open up. It was weird because I was so nervous going into it. I was thinking about how I was at that age, and it felt really important for me to show them that I don’t have it all figured out either. Everyday I’m still questioning myself; trying to figure out my own identity.

The project culminates in the tapestry and two accompanying flags, as well as a poem written by Shaw. In addition, there is a film and exhibition, produced in collaboration with CircleZeroEight and Flannels on from 3rd May to 4th May.